When you make gadgets for work as well as for fun, it’s almost inevitable that you end up with a cornucopia of random parts taking up space in all manner of random bins and boxes. I was overdue for a project that was just for fun, so I decided to see what I could scrape together into a coherent whole. I had recently purchased a Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W in an attempt to make a tiny web-browsing PC out of it, but then found out that the little Pi didn’t even have enough memory to handle a modern web browser. Additionally, the 7″ screen that I bought to accompany it had a resolution of 1024×600, which I had originally thought would be sufficient because many websites seem to be optimized for narrow, vertical viewing. There ended up not being enough resolution — even some apps that came with Raspberry Pi OS struggled to fit into those cozy confines.

For a while now, I’ve wanted to play some of my classic Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo games with my kids, but I haven’t been brave enough to actually bring out my consoles and leave them at the mercy of curious little hands. One solution would be to simply install some emulators on one of our computers, but that wouldn’t quite capture the magic of sitting in front of a TV with controllers tethered to the console. With enough surplus hardware in hand, I finally had an excuse to design something convenient enough use and relocate on a whim, but that maintained at least a facade of the 16-bit console gaming experience. I call the result the Retrovision Z2W.

Since this was meant to be a just-for-fun project, I made it a goal to only use pre-made components for the electronics. Between what I had on hand and what I found at my amazing local makerspace’s donation rack, I had almost everything I needed. All I had to do was focus on a 3D printed case to hold everything together.

While I originally considered giving the Retrovision a wall plug so that it could only be operated from an AC outlet, I thought that maybe I should stick to the aspects of classic gaming that made it charming and fun rather than adding undue restrictions on its use. In the end, I decided to use a USB-C panel passthrough on the back of the unit so that it could be powered from a power bank, or, if one desires, from a 5V wall wart.

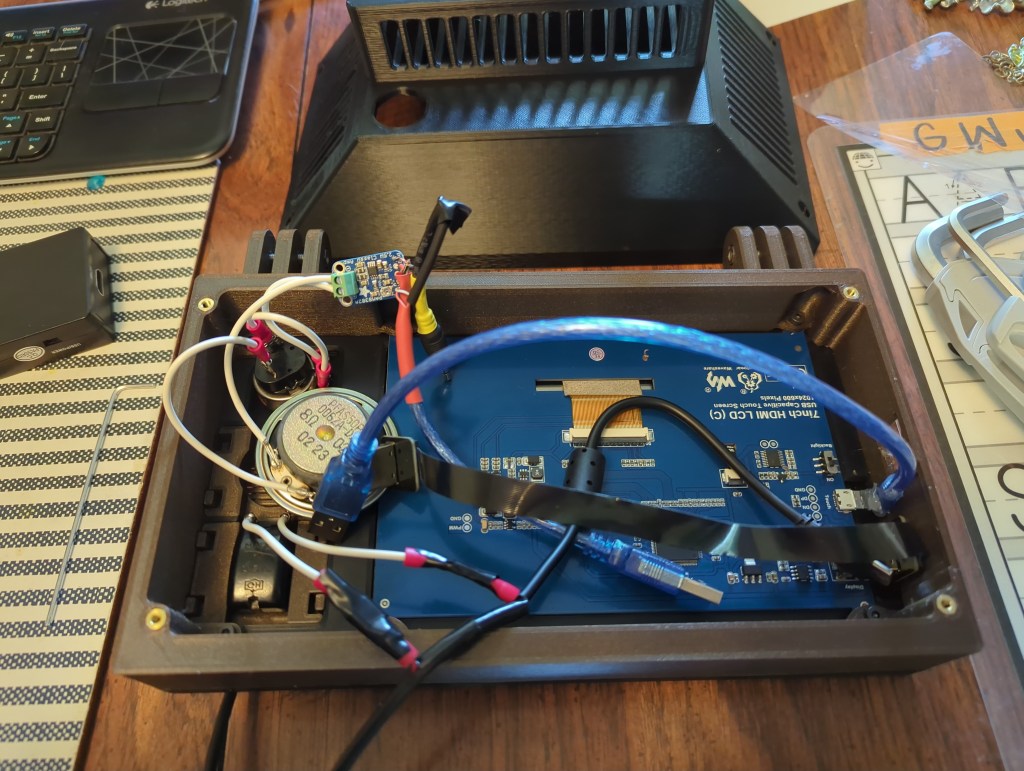

If I was starting this project from scratch, I would have used hardware with an audio output built in. Since I was mostly working with what I had on hand, I had to buy a few extra parts to make the sound work. The screen had an HDMI input but no audio output, so my workaround was to instead feed the HDMI output of the Pi to an HDMI audio extractor. This passed the video to the screen, while giving me an headphone jack to plug my speaker into. Unfortunately, the headphone jack only provided line level output, which is good enough for headphones but not enough to drive anything bigger, so I bought a little audio amp breakout board to rectify that little issue.

CAD Design

As with many projects, I started working on the 3D models for this one in FreeCAD. Unfortunately, as with many projects, I hit a point where the difficulty of working around the quirks of the current FreeCAD user experience pushed me toward another established CAD system. (In this case, rounded corners projected onto to sketch were a nightmare to turn into usable geometry. I hear that V1.1 addresses this issue, which I’m excited about) Previously, my main alternative would be Alibre, but I no longer have any machines running Windows, so I tried out the web-based OnShape to see whether I could finally put Fusion/Alibre/SolidWorks to rest for good. While I don’t prefer for my data to be kept in the proverbial cloud, I do think that OnShape is otherwise a fantastic piece of software. The fact that one can access it from any computer capable of running a modern browser is great for anyone that might not have access to a powerful PC. It may well become my program of choice for professional work.

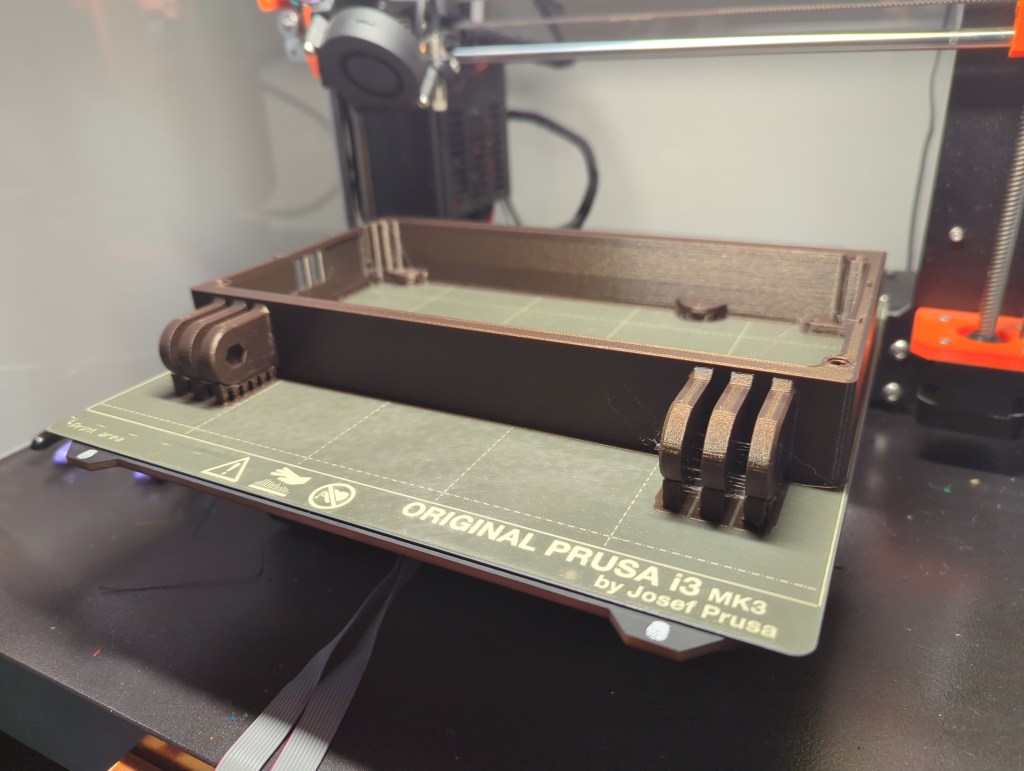

When deciding how large to make my little gaming box, my lower constraint was the size of the screen, and the upper limit was the size of the print bed on my Prusa. Fortunately, printing as wide as possible on my 3D printer gave me just enough room for the screen and some old-timey switches and knobs on the side.

Since I knew that this was going to be carried around the house by little hands, I decided to add a handle to the top of the system that was sturdy enough to withstand some abuse and prominent enough to be the obvious way to pick the thing up. That way it’d be easy to pick it up with one hand while holding a still-connected controller in the other.

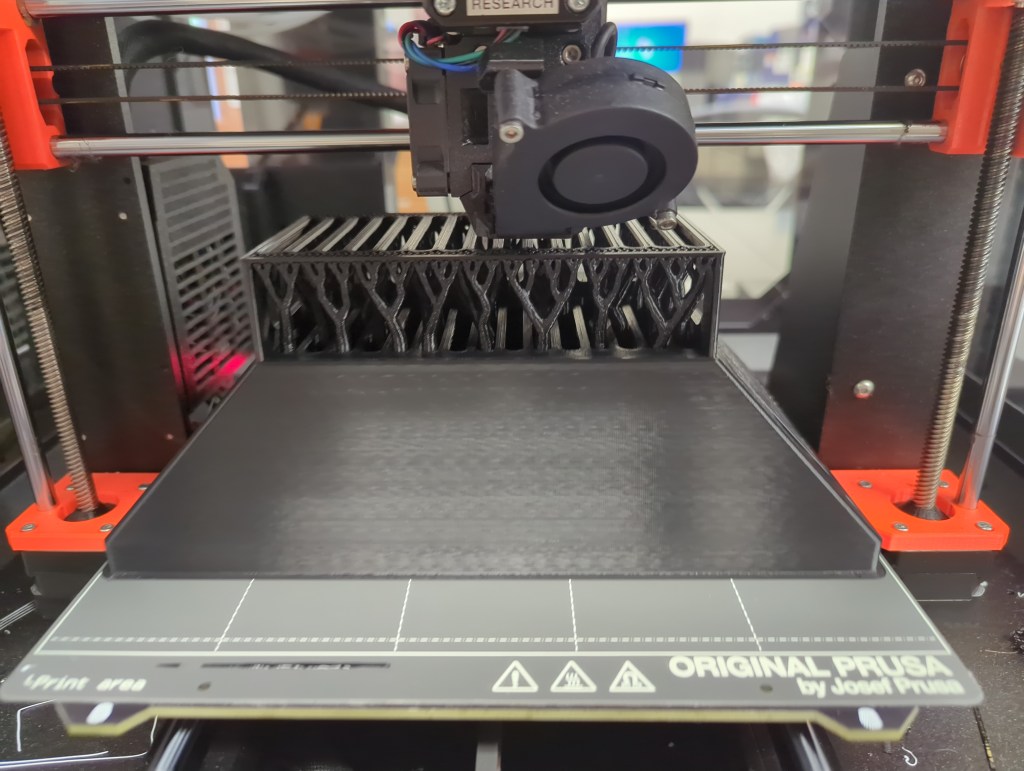

I try to make my designs as easy to put together and operate as possible, the fancy term for which is “design for manufacturing“. When designing something, it’s important to think about the tools that you’ll be using to build your gadget/tool/sandwich/etc. In my case, the enclosure was going to be entirely 3D-printed on a desktop FDM machine, so one thing I needed to make sure of was that my parts could either be printed unsupported, or in an orientation that allowed for breakaway support. The exterior of my little CRTish TV lended itself well to this process by and large. Thankfully, I was able to use breakaway supports when necessary. The back of the enclosure needed some happy trees in order to complete its back surface.

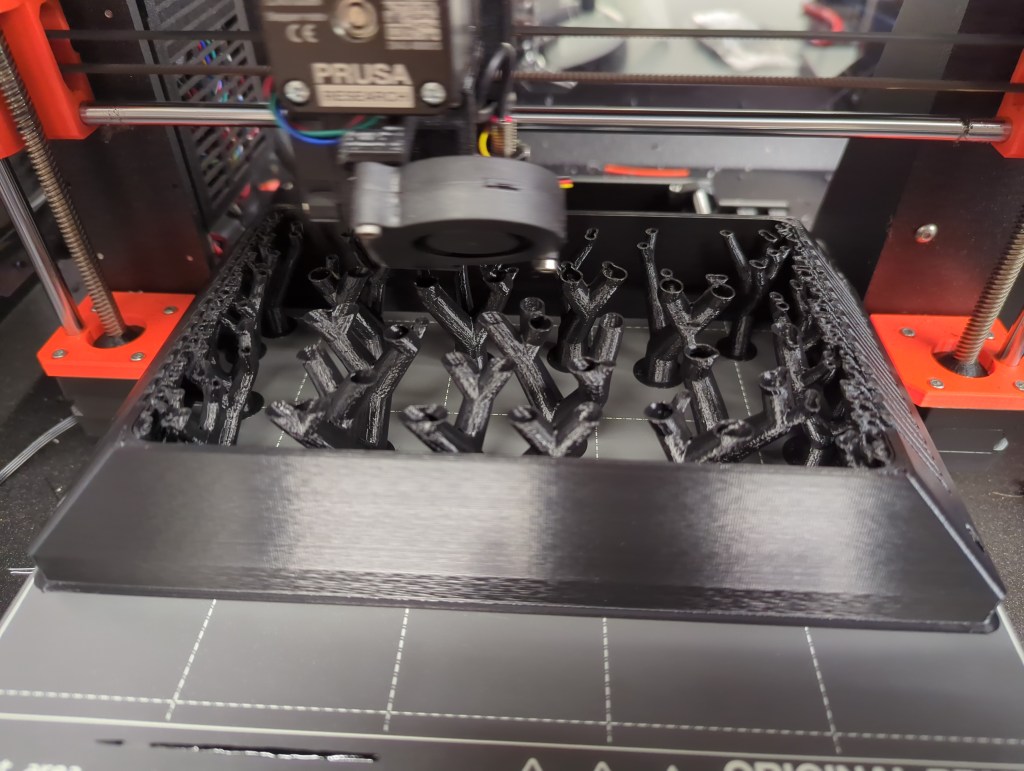

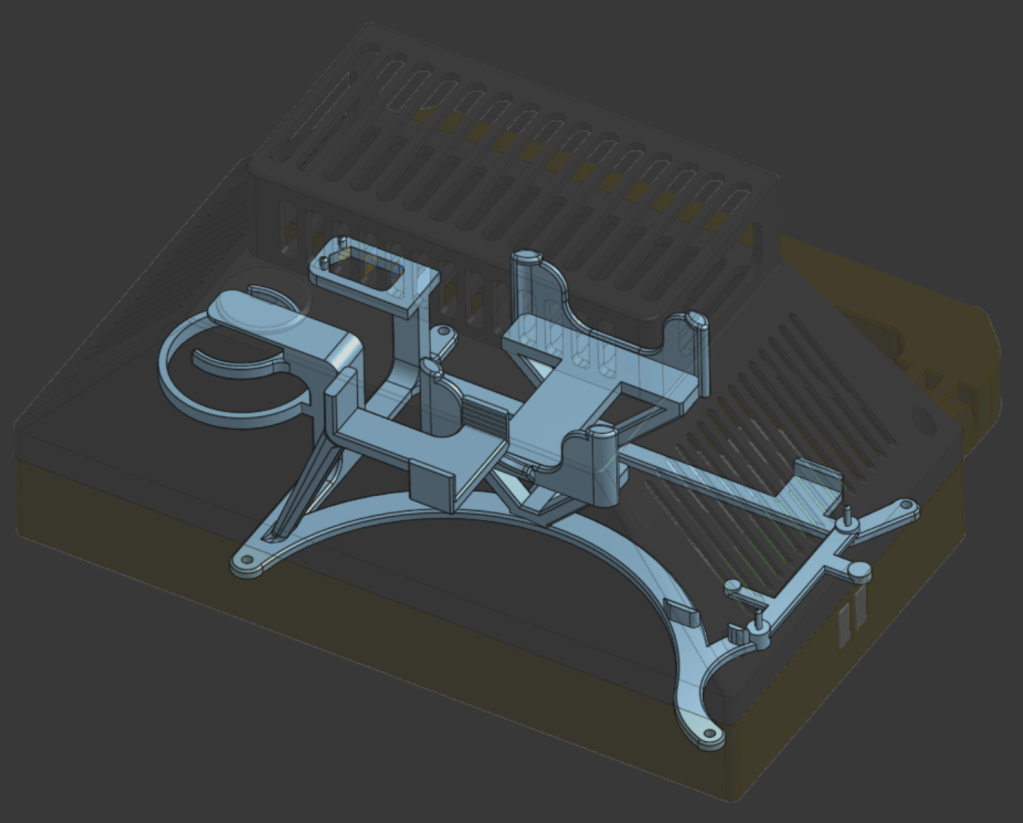

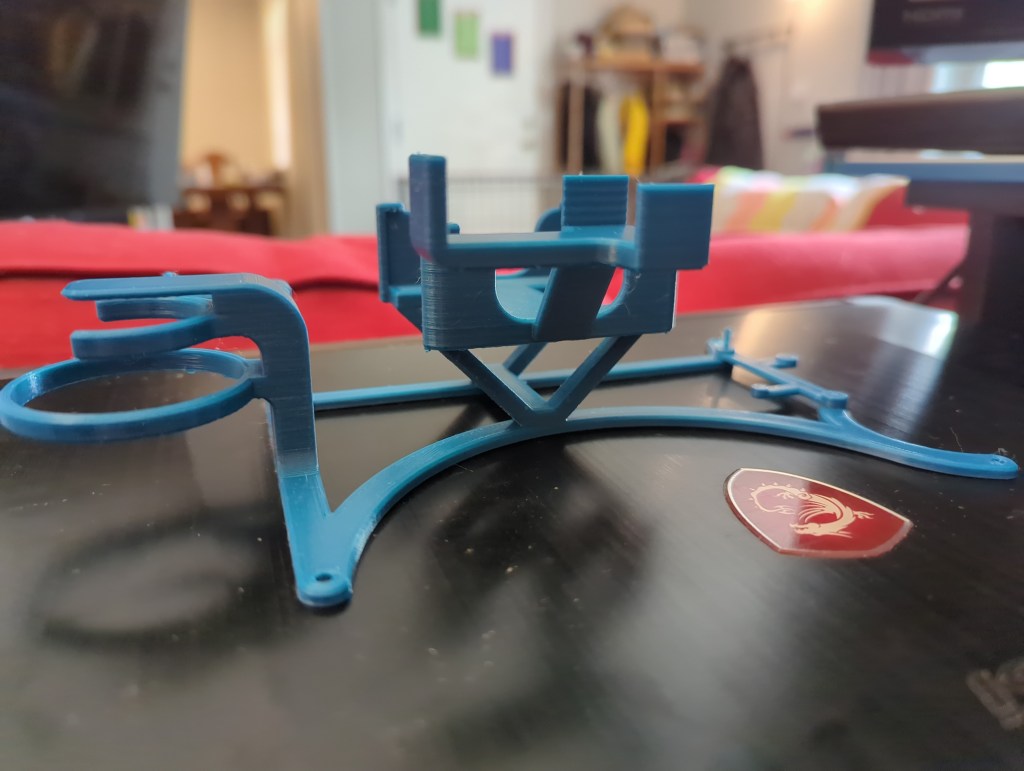

Inside the case, I had the option of simply cramming all the electronics into the big empty internal space of my design, but I wanted things to be just a tad more orderly, so I designed a “skeleton” to hold all the electronics in place. This part really took full advantage of the idea that “complexity is free” in 3D printing, and while it was a bit finicky to break off all the supports afterward, it made routing my wiring a whole lot easier, so it was very much worth the time.

Onshape worked well for my preferred CAD workflow, which involves moving all my known parts to their correct places in space and then building whatever else I need directly off of them. If you ever start making CAD models this way, always make sure that all your sketches and assembly joints are fully constrained, otherwise your entire model might accidentally blow up on you in exotic and unexpected ways. It takes less time to shore up a model as you go than it does to be unable to fix a blow-up and have to start from scratch, as I’ve learned over the years.

Iteration

Thankfully, this design came together pretty smoothly. The main thing I iterated on was the look and feel of the front. I switched from a smooth to a textured print bed, and chose the darker of two brown filaments I had on hand. I designed the small brown inserts for the power switch and sound hole to be removable and interchangeable, but the original tabs I drew up proved too weak to be made with FDM, so I made a second design that was more robust. Getting the corners of the front panel not to curl also turned out to be a challenge when I switched to the textured build plate. I increased the bed temperature and closed up the printer enclosure, which didn’t completely resolve the issue, but at least reduced it enough that it almost looked like it was part of the TV-inspired design.

The volume knob went through a few iterations as well; both the knob that you see on the outside and the potentiometer concealed underneath changed from the start of the project to the end. The longer I rummaged in the spare parts bins, the more fantastic candidates I found. in the end, I chose a slightly smaller knob that fit the case better than the giant original one I found, and a potentiometer that had a built-in push-pull switch so that I had the option of muting the system entirely.

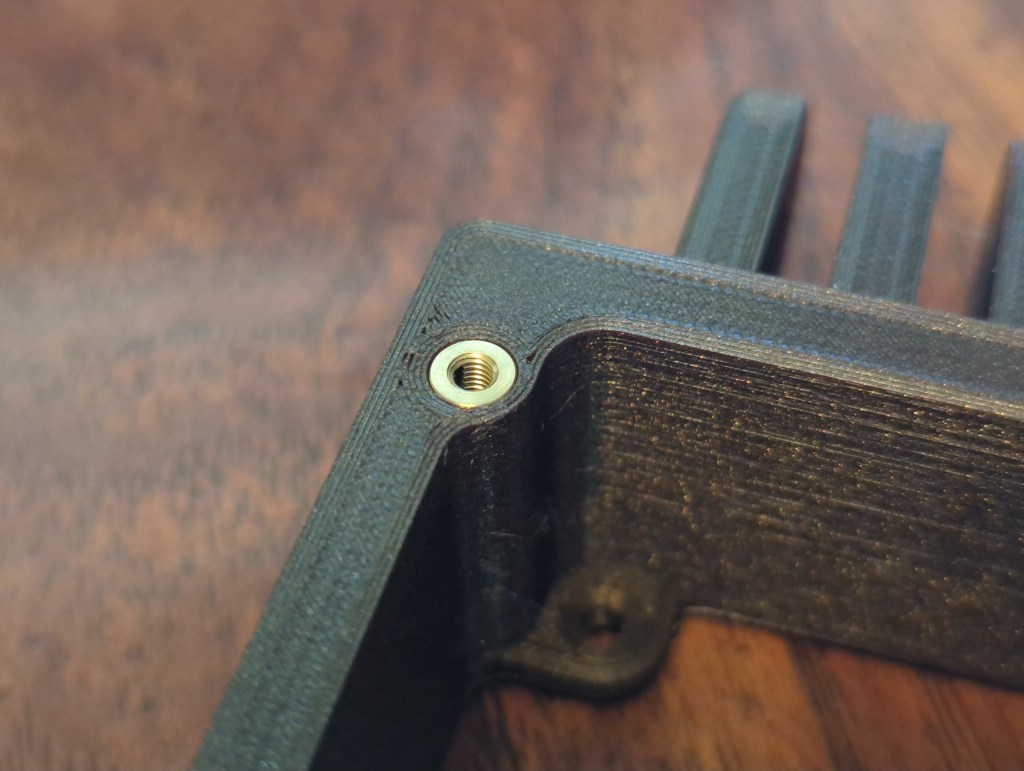

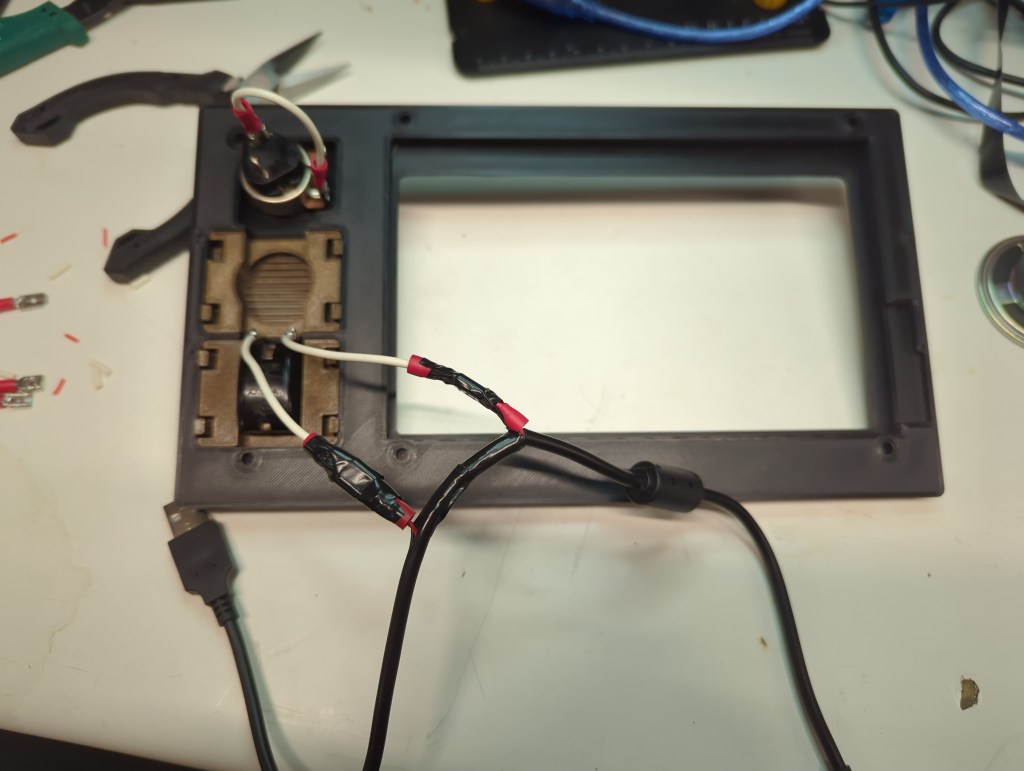

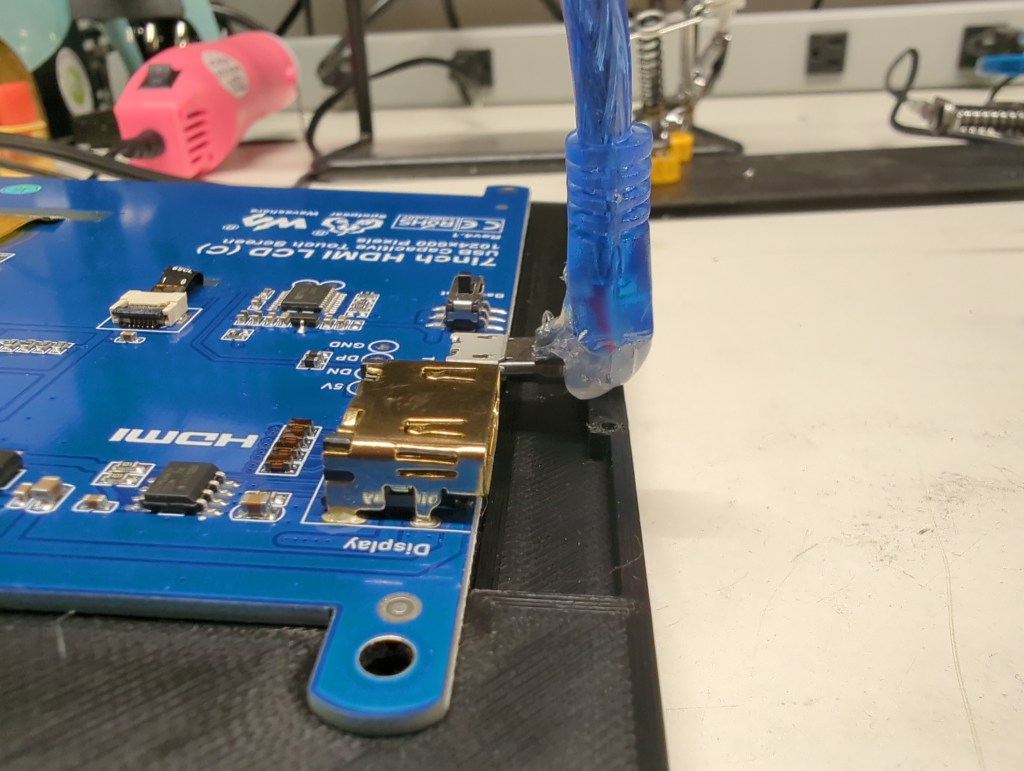

Assembly

I designed the Retrovision to be assembled from front to rear. That way, I could place the front part of the case face-down on the workbench and assemble the whole unit without needing to reorient it multiple times. I don’t have a special soldering iron tip for installing threaded insert, so instead I rested them on my Pinecil for a few seconds before melting them into place via their pilot holes in the prints. I did have to hack apart a few USB cables: The USB cable providing power for the whole unit had to have a power wire cut so that I could turn the system on with the old toggle switch mounted to the front; The cable providing power and a data connection for touch input to the LCD needed to have its molding cut on one end to squeeze the cable into the tiny amount of space I had available to me between the screen and side of the case; and a third cable had to have one end chopped off so that I could route power from the USB hub to the audio amp. All of these hacks could have been avoided if I was designing this product to be produced commercially from the ground up, but since I was just having fun with (mostly) what I had on hand, getting the wire cutters and spade connectors out was no big deal.

Controllers

I wanted to give my kids a chance to have a stake in making this system, so I looked online hoping to find a controller kit that they could put together. As luck would have it, Handheld Legend sold exactly what I was looking for. I just had to do some light soldering when first receiving the kit, but the kids got to pick out and print their own button and case colors and put it all together. They got to build their first functional electronics, and we all got to play video games together. Win-win.

Software

I installed Retropie. It worked right out of the box. I added my games and was all set. The open source community is a truly indispensable asset to all makers.

Thoughts

Overall, I’m thrilled with how this project turned out. Between finding a purpose for parts that might otherwise end up collecting dust indefinitely and incorporating scavenged old switches for a proper tactile experience when turning the system on or adjusting the volume, this little system is just what I was hoping to get out of the experience. The resolution of the screen is just fine for displaying old games, and the single speaker I saved from the trash can sounds exactly as good as it looks like it should.

Would I send this design off for mass production? Nah. If that was the plan, I’d start fresh and remove the vast majority of the internal wiring that this one required. That was never the intent here, though. I got to turn some assorted stuff into something that will hopefully create some fun memories for my kids and me.

Links

Parts List

| Part | Price | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Raspberry Pi Zero 2 W | $15 | PiShop.us |

| Pi Zero Heatsink Case | $8.95 | PiShop.us |

| Waveshare 7″ Touch LCD | $43.99 | Waveshare |

| Handheld Legend Opencontroller kit x 2 | $19.99 x 2 | HHL |

| Audio Amp | $3.95 | Digikey |

| HDMI Audio Extractor | ~$11 | ~the internet~ |

| Right angle HDMI-to-flat-cable plug x 2 | $6.50 x 2 | Digikey |

| Flat cable | $1.95 | Digikey |

| USB panel passthrough | $5.95 | Digikey |

| 30kOhm potentiometer with push/pull switch | Free! | found in a parts bin at my makerspace |

| USB hub | Free! | found on my makerspace’s donation rack |

| Old toggle switch | Free! | found in a parts bin at my makerspace |

| Speaker | Free! | found in a parts bin at my makerspace |

| M3 threaded inserts | Freeish | McMaster, but I already had an old pack |

| M3 bolts, 10mm and 25mm | Freeish | McMaster, but I already had old packs lying around |

| M4 Bolts, 25mm | Freeish | McMaster, but I already had an old pack lying around |

| M4 nuts | Freeish | McMaster, but I already had an old pack lying around |

| Assorted USB cables | Free! | They’re everywhere |

| Proto-Pasta Double Espresso Metallic Brown HTPLA | ~$10 of filament | Affiliate link! (Use NOODLENOOB for 10% off) |

| Proto-Pasta black PLA | ~$5 of filament | Affiliate link! (Use NOODLENOOB for 10% off) |

| Power bank | Free, in a sense | Already have some on hand |

Leave a comment